Painting the Cowpasture River

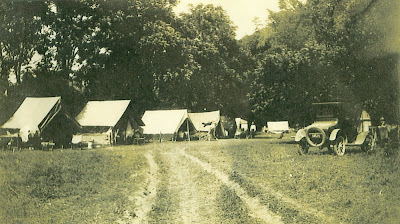

Long before I was ever a painter and looked at things with a painter's eye - before I even knew what a painter was - I knew and loved the Cowpasture River. Each July, on the first Friday after the 4th, from the time I was a boy, my father and I would leave Lynchburg and wind over the hairpins of Route 501, heading west for Bath County, Virginia, and the Cowpasture River. He and I, and a small army of other fathers and their sons, were reenacting a ritual that began in the early part of this century when the first group of Lynchburg men began journeying by train to Clifton Forge, and from there, by wagon and Model-T over the dirt and gravel path that is now Route 42, to camp and fish along the banks of the Cowpasture.

Over the years a small camp evolved. Army tents, pitched on the ground, gave way to wooden tent decks, then to small screen enclosures, and small cabins. The roads were improved. Families began to join the procession.

Conditions were basic and rustic. My father's generation loves to tell stories of the old days before running water or flush toilets. Even into the 1960's, my generation remembers the magical time before electricity came, when we read books or played games by the flickering orange light of kerosene and propane lamps, and drank mouth-numbing sodas from Depression-era ice-boxes filled with huge, slick blocks of crystal clear ice that an ice company in Clifton Forge, now long gone, used to truck in.

I continue to this day to return to the river as to an earthly Valhalla. I would not be surprised if just beyond St. Peter's gate the Cowpasture River came into view. But now I am a veteran of fifty summers, and other motives mingle with the former ones to bring me there. I still go to the river to enjoy its benedictions, but I also go there to ply my trade - to prospect for paintings. Although it's pleasant working on the Cowpasture River, it presents me with a unique difficulty: I have trouble seeing it at all.

As anyone who seeks to do a particular job must learn to see and think in the specialized terms of that profession, a painter, in order to do the job of painting, must learn to see and to think as a painter. Claude Monet, the great Impressionist, defined the painter's challenge this way:

"When you go out to paint, try to forget what objects you have in front of you, a tree, a field... Merely think, here is a little square of blue, here an oblong of pink, here a streak of yellow; and paint it just as it looks to you, the exact color and shape, until it givees your own naive impression of the scene."

Monet often said that he wished he'd been born blind and then had his sight restored so that he could see pure sensations of color, unencumbered by meaning.

Now I am painting along the river bank, looking toward the camp. This is my problem: how does that streak of yellow over there stop being the Big Dock, where my cousin Graham used to entertain us younger kids with his antics, imitating a man, perhaps Clyde Barrows, getting shot repeatedly before falling into the water? How does that dark greenish shape over there stop being the stretch of quiet water below camp where the white-trunked sycamore trees shade the surface, the place where John Owen, my first patron, loved to cast his fly line?

Wherever it is that one paints, it is a struggle to see things on their own simple, visual terms. Meaning is the conjugal partner of sensation. The two do not want to be teased apart, to be disentangled, the way that painters seek to do. At the Cowpasture River, every sensation sets up a ripple of memory and association. I struggle to keep my professional distance. My subjects hide from me behind a thick, shifting gauze of memory. When I paint the Cowpasture River I am never alone. I am surrounded by ghosts. I meet shades of myself and the people I have loved at every turn. The mirthful sound of laughter rings in my ears. The acrid smell of kerosene smoke is in my nose. The taste of ice-cold grape soda is keen on my tongue.

Over the years a small camp evolved. Army tents, pitched on the ground, gave way to wooden tent decks, then to small screen enclosures, and small cabins. The roads were improved. Families began to join the procession.

Conditions were basic and rustic. My father's generation loves to tell stories of the old days before running water or flush toilets. Even into the 1960's, my generation remembers the magical time before electricity came, when we read books or played games by the flickering orange light of kerosene and propane lamps, and drank mouth-numbing sodas from Depression-era ice-boxes filled with huge, slick blocks of crystal clear ice that an ice company in Clifton Forge, now long gone, used to truck in.

|

| Courtesy of Jim Thomson |

|

| Courtesy of Jim Thomson |

|

| John Owen, second from left. Courtesy of Jim Thomson |

I continue to this day to return to the river as to an earthly Valhalla. I would not be surprised if just beyond St. Peter's gate the Cowpasture River came into view. But now I am a veteran of fifty summers, and other motives mingle with the former ones to bring me there. I still go to the river to enjoy its benedictions, but I also go there to ply my trade - to prospect for paintings. Although it's pleasant working on the Cowpasture River, it presents me with a unique difficulty: I have trouble seeing it at all.

As anyone who seeks to do a particular job must learn to see and think in the specialized terms of that profession, a painter, in order to do the job of painting, must learn to see and to think as a painter. Claude Monet, the great Impressionist, defined the painter's challenge this way:

"When you go out to paint, try to forget what objects you have in front of you, a tree, a field... Merely think, here is a little square of blue, here an oblong of pink, here a streak of yellow; and paint it just as it looks to you, the exact color and shape, until it givees your own naive impression of the scene."

Monet often said that he wished he'd been born blind and then had his sight restored so that he could see pure sensations of color, unencumbered by meaning.

Now I am painting along the river bank, looking toward the camp. This is my problem: how does that streak of yellow over there stop being the Big Dock, where my cousin Graham used to entertain us younger kids with his antics, imitating a man, perhaps Clyde Barrows, getting shot repeatedly before falling into the water? How does that dark greenish shape over there stop being the stretch of quiet water below camp where the white-trunked sycamore trees shade the surface, the place where John Owen, my first patron, loved to cast his fly line?

|

| Courtesy of Jim Thomson |

Wherever it is that one paints, it is a struggle to see things on their own simple, visual terms. Meaning is the conjugal partner of sensation. The two do not want to be teased apart, to be disentangled, the way that painters seek to do. At the Cowpasture River, every sensation sets up a ripple of memory and association. I struggle to keep my professional distance. My subjects hide from me behind a thick, shifting gauze of memory. When I paint the Cowpasture River I am never alone. I am surrounded by ghosts. I meet shades of myself and the people I have loved at every turn. The mirthful sound of laughter rings in my ears. The acrid smell of kerosene smoke is in my nose. The taste of ice-cold grape soda is keen on my tongue.

Frank, interesting bit of personal history here.

ReplyDeleteMy take on what Monet said is that looking for disembodies spots of color is only part of painting. It was a quote probably promoted by so many art historians of Impressionism because it encapulated in a few words a big part of Impressionist philosophy.

As long as one's associations with the places or people one is painting don't short circuit one's looking and seeing, I bet they're more helpful than not. We're drawn to subjects for a host of reasons- some purely visual, others more emotional and psychological. It's all ok.

Nice piece, Frank. If those last photos are yours, you don't have any trouble "seeing" it --- seeing is a very personal thing, and your vision, translated into paint, is luscious.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Judy.

ReplyDeletePhil, the whole business of seeing vs. knowing is rich with paradox, for sure, and one which I thoroughly enjoy!

ReplyDeleteThat is, when it's not driving me mad...

ReplyDeleteCezanne's back-handed compliment, "Monet is only an eye, but what an eye!" did Monet a disservice because it implies that seeing is a mechanical act, when we all know there are emotional and psychological dimensions to the process. The statement achieved a certain desired distancing from the objectives of Impressionism, but I think it's fundamentally erroneous. It robs Monet of the emotional connection and warmth that he assuredly felt for his subjects and that he translated into his paintings.